This month aural ethnographer Dr. Milena Droumeva argues for the role of acoustic ecology in filling key gaps in the way that contemporary digital media scholarship has addressed audio-based social media. -RJ

__________________

By Milena Droumeva

Over the last 13 years I have been involved in acoustic ecology, soundwalking, sound design and research including writing, producing and thinking through sound. In the past five years I’ve also increasingly questioned the role and lessons of acoustic ecology and in particular its applicability to a contemporary instant-gratification, media-driven ‘networked publics’ (Ito et al., 2012) set in metropolitan contexts filled with urban noise pollution alongside carefully crafted consumer sonification. For those of us in sound studies, urban soundscapes and aural ecologies draw the bulk of our attention; the net is presumed to be ’silent’. But is it? The convergence of ubiquitous mobile computing with active social networking has made the online world a highly sensory-rich place with photos, video and audio snippets being used in place of textual communication. The question is, have the aesthetic politics of the smartphone and social networks made us better able to perceive our surroundings visually and aurally? Where does acoustic ecology fit inside the material conditions of new media culture?

According to Schafer (1977) attentive listening is the best foundation for good acoustic design – after all, if we committed as a society to pay more attention to sound, to cherish and protect important regional and historical soundscapes, the urban environment would be a lot less noisy, with less acoustic masking, and we wouldn’t have to go to such lengths to tune out our daily surroundings. The purpose of soundscape awareness activities such as soundwalking (on the more accessible end) and soundscape composition (a more specialized and technologicallymediated approach) is to evoke interest, appreciation and ultimately better urban design through direct engagement with the soundscape. In my personal experience, soundwalking in Vancouver over the past decade has been primarily an exercise in learning to appreciate and aestheticize the sounds of traffic, vents, construction, crowds and background music. Refusing to accept a ‘nature is good and cities are bad’ duality of acoustic balance leaves us with the task of contenting with urban soundscapes by finding ways to stay connected aurally and ultimately effect transformation of some kind, if not material, at least attitudinal.

For those who dwell in the city, soundscape awareness, and by extension, acoustic ecology, is about listening attentively to what ‘is’ there, learning to understand the composition of each soundscape, the function of individual sounds, and by extension, to evaluate their sustainability as sensory participants in a local ecology that includes the listener and the soundscape (Schafer, 1977; Truax, 1984). Finding silence, or at least an acoustically ‘balanced’ listening experience in an urban center such as Vancouver has meant going outside the borders of the city, out to parks, hikes, lakes, islands. As I haven’t been able to really appreciate some of the cornerstones of city noise (a problem worsened by aging) I have also had an increasingly harder time sincerely convincing sound students or members of the public that they too should attentively listen to the raucous of urban soundscapes. Instead, I can relate to practices around the management and regulation of unwanted sound including seeking quietude, using headphones or earplugs to substitute my own musical choices (DeNora, 2000; Bull, 2007), and ultimately venturing to the great outdoors to ‘recharge my batteries’. Soundwalking in the city is instead valuable as a practice of mindfulness, not so much in terms of listening but in terms of not talking; not contributing sonic or psychic energy to the already-too-busy surrounding environment.

One of the ways to engage with sound, promoted from within acoustic ecology itself, is through field recording and soundscape composition. With the ubiquity of communication technologies that are fully recording-ready, it is worth questioning whether field recording can become a practice as ‘everyday’ in nature as listening to music, texting and taking pictures. In other words, will there be an ‘Instagram for Audio‘? As an avid smartphone adopter, audio recording enthusiast and sensory ethnographer; and after much perusing of the online multiverse for audio-friendly social networks; I offer that this just won’t happen, and this piece is a commentary of sorts, to a handful of articles that herald every next smartphone audio app the ‘Instagram for Audio’. Through decades of audio technology becoming more portable and accessible to non-specialized publics, field recording – the recording of ‘found’ environmental sound, has remained a niche hobby. The story of ‘everyday photography’ is markedly different. As cameras have become over time more affordable and easier to use, the practice of recording private everyday moments through images has become entrenched as a cultural trope of collective identity representation and a must-have for every household. While home audio and video recording devices bring an ‘auditory’ dimension into the visual rhetoric of family moments, it is the practice of hobbyist ‘landscape’ photography that is most analogous to environmental sound recording. Leveraging the explosion of social networks and their emergent role as public ‘galleries’ of everyday identity and sociality, Instagram launched in 2010 as the first image-based social network. Its unspoken promise to transform everyone into a ‘professional’ photographer by allowing the selection of several ‘artistic’ filters and a custom soft-focus lens effect, has earned Instagram upwards of 300 million active monthly users (as of December 2014). More importantly, in my view, Instagram has helped facilitate and promote a kind of aestheticization and representation of environmental and contextual everyday ‘moments of significance’, ranging from landscapes, street corners, coffee shops, food and other natural settings, all the way to war zones, public protests and mass demonstrations.

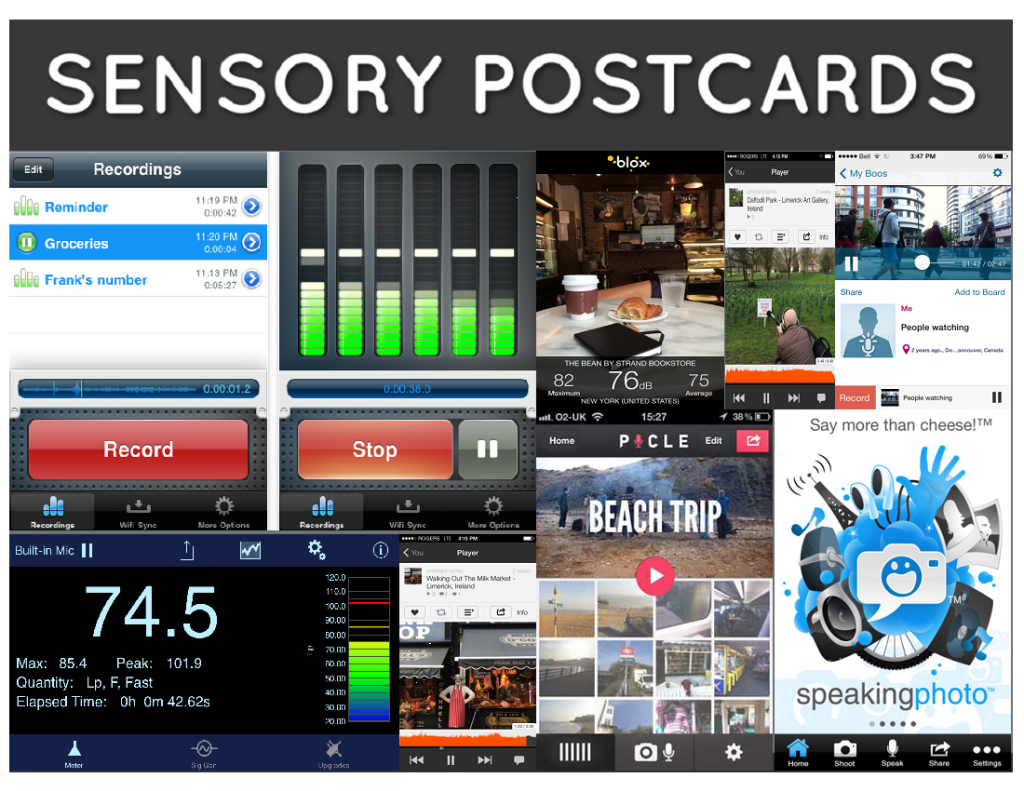

My mission for the past five years has been to investigate how and whether mobile technologies for communication are in the process of engendering a similar shift in terms of a widespread adoption of audio recording practices, hopefully resulting – to reference the framework of acoustic ecology again – in a more critical and astute appreciation of and engagement with our sonic surroundings. First, an inventory of what is there currently for the everyday production of what I would call ‘sensory’ or ‘aural postcards’: in the sphere of social media, there are several specifically audio-based social networks, notably Dubbler (now Yappie) and Hubbub, neither of which are ’thriving’ or in any way geared towards environmental or field recordings. There are also several ‘sound photograph’ communities via applications such as Picle (now dead), Samsung’s built-in Sound and Shot, and SpeakingPhoto, which combine static image with 5 to 30 second audio recordings. There are a number of tools for iOS and Android, for the measurement of decibel levels, including several that combine a photograph with dB readout overlay (dB and Blox for the iPhone). The apps for audio recording are too many to make mention of, with the important note that most smartphones and every major operating system include a built-in voice recorder. In terms of grass-roots attempts to organize global field recording communities through ’soundmapping’ initiatives, radioAporee has a sizeable history, with more contemporary contenders such as Foundbite for the Windows phone, Sound Around You and FoundSounds for the iPhone, HASTAC’s long term initiatives around local mapping projects, as well as the audio networks Audioboo.fm and Soundcloud.com. A quick survey around these tools, however, reveals a similar picture: there is dense content and participation in specific localized areas, with sporadic entries elsewhere. Even in the face of ‘global’ intentions, huge chunks of the world remain ‘silent’ in these communities. Not exactly a ‘world’ soundscape project.

In an effort to explore how people might approach encountering their everyday urban lives through the modality of sound, I created, as part of my dissertation work at SFU, a small case study with ten people, each provided with an iPod Touch, and asked to collect ‘aural postcards’ of their daily life for two weeks. Using audio, video, images and decibel measurements, participants recorded a sort of typical distribution of spaces and contexts from of their daily routine including domestic spaces, urban and nature outdoor environments, sounds of transportation and movement, cafes and restaurants, exercise and shopping. It should be noted here that whereas social media recordings involving sound (audio and video clips) tend to feature voice and conversations, most of these recordings highlighted sound environments over speech and very few featured conversations. This, as a trend, is more akin to the way we use social media linguistically and visually – through short-code, inter-textual references and instantaneous impressions, ‘pointing to’ rather than describing, ‘flashing’ meaning rather than explaining. Also of note is that participants relied heavily on ‘sonic highlights’ – shorter aural snippets meant to give a sense of the sonic character of an event or environment; less often was an entire event or process recorded and verbally annotated on location. This is another trend consistent with typical approaches to social media broadcasting, and a trope well established in the format structure of mass media as the ‘soundbite’. In other words, we use everyday media production to highlight things in ways that are subjective, less so to give thorough and complete accounts.

While not above critique or reproach (which we’ll leave for another occasion), Instagram has nevertheless influenced and possibly shifted the way most people experience everyday surroundings visually and how we see beauty and artistry in the mundane (there are even infographics about ‘what using your favorite Instagram filter says about you‘). In a similar way, my sonically-focused case study made people more attentive to the sonic characteristics of typical domestic events, as well as to the qualities of predominant urban environments. In their own words, the activity of creating aural postcards sent people on auditory treasure hunts for ‘cool’ and ‘interesting’ sounds and arose their listening attention throughout the day:

[the study] made me more mindful, even if it was an afterthought at the end of the day. Like thinking about ‘what sounds did I encounter today?’ and ‘what sounds might I record tomorrow?’, even in the moment, like having to think about why a sound was interesting to me, made me notice it more on an ongoing basis.

To me, this quote demonstrates particularly clearly the role that technology played in this process of listening – even without the device, participants listened to their everyday soundscapes in terms of them being ‘recording-worthy’ – an extension of Daisuke and Ito’s (2003) suggestion that camera phones re-define private, routine, ordinary moments as ‘picture-worthy’. In one sense, this seems like a ‘win’ for acoustic ecology and the practice of ‘attentive’ listening. Yet the comparison with Instagram hits a wall right about here. Several participants noted that even though they thoroughly enjoyed the experience of creating a multimedia archive of everyday sounds, including documenting and analyzing sound environments, they noticed their attentiveness for listening waned over time, even in a two-week period. None envisioned recording everyday sounds ongoingly, and in fact, none have carried on with regular audio recording activities using their own devices. One of the big reasons for this is that, as participants noted themselves, the primary urban condition in sonic terms is noise; that is, listening attentively in the city actually brings about negative connotations. The topic of noise and recordings of noise featured prominently in many participant accounts and virtually everyone expressed some level of displeasure with the most common contributors to city noise: traffic, electric hums and drones, busy commercial establishments, construction and machinery.

In order to be ‘Instagram for audio’, a mobile recording application has to be able to do for sound what Instagram does for image – aestheticize and transform visual moments in simple yet effective ways and provide a forum for the social curation of everyday experience. In terms of listening, while our ears can easily do this work – zoom in on a sound we appreciate in the environment, pull it out and aestheticize it by bringing in a range of familiar associations, the microphone is woefully agnostic and rarely does justice to the sonic characteristics we ideally want to highlight. An ‘Instagram for audio’ would have to not only bring out certain sounds or sonic situations, but also enhance or aesthetically render their qualities in some way beyond subjective appreciation. In thinking about the context of social media, there is another problem. Since most of this kind of everyday media is produced and consumed on mobile devices, the settings in which one would listen to ‘sonic Instagram’ entries would often be noisy and distracted – not the ideal context to listen to soundscape compositions of this kind. The closest mobile application contender with the potential to popularize field recordings as social media communication on a mass scale, was, in my experience, RJDJ: an ‘augmented reality’ app that takes microphone input, transforms and re-mixes it into a real-time soundscape composition. Yet the reality is that RJDJ’s online community remained staunchly small and eventually the company discontinued their field recording app and focused development on location-delivery of commercial music.

But there is an even more subtle reason why I can’t see people communicating with each other through environmental sound recordings on a global scale and as an integrated, social, everyday practice.

It’s about time.

Listening takes time. Adopting a conscious attentiveness to sound literally requires staying in a place and in the moment for a while. Whereas a sight can be perceived and appreciated in an instant, attending to sound means attending to the unfolding of time, hearing changes and shifts and relationships. This is not to essentialize a sound-sight duality or say that we can’t or don’t experience the visual environment in this way; simply that it’s not how we ‘Instagram’ it. One of the big draws to Instagram is also one of its more sober critiques, and that is the instantaneous visual gratification of snapping a pic and moving on, where the artefact takes the place, in a sense, of the actual experience. As one participant in my study put it, taking pictures is fast and convenient and so she has a giant visual archive, but she hardly ever looks through it; photos are ultimately not representative of the emotion or feeling at that specific time and place. Sound recording gets at that a lot better but it’s an investment: an investment, which has proven to be just outside the narrative of new media culture. Even just looking at e-commerce trends in social curation, while audio-based networks are plummeting and mobile soundmapping initiatives stagnate, Twitter launched Vine, a 6-second video/audio app; the duration based on metrics of current and projected use. Instagram swiftly introduced (and subsequently outperformed Vine) its own video component with up to 25 seconds of video/audio airtime. In essence, none of the social media giants expect you, the producer and listener, to audio record anything longer than half a minute.

I am not sure where this leaves the practice of everyday audio recording as a form of participation in new media culture, and I’m not sure where this leaves acoustic ecology in terms of a potentially technologically-mediated soundscape awareness. Perhaps we should celebrate the, albeit modest in comparison to visual curation networks, new mobile participation in a variety of activities around the recording and distributing of sound and music (Thulin, 2013). Perhaps soundscape engagement is fated to be a localized and participatory practice and not a global, web-based trend, as evidenced by a number of community-led soundmapping, soundwalking and field recording projects (Järviluoma, 2009; Uimonen, 2011). And maybe soundwalking has to remain a personal, subjective, local and un-mediated experience of mindfulness and presence. But if you have a smartphone, grab it and go out recording.

Works Cited:

Bull, M. (2007). Sound Moves: iPod Culture and Urban Experience. London: Routledge.

Daisuke, O. & Ito, M. (2003). Camera phones changing the definition of picture-worthy. Japan Media Review. Retrieved from http://www.ojr.org/japan/wireless/1062208524.php

DeNora, T. (2000). Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Ito, M. et al. (2010). Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Järviluoma, H. (2009). Soundscape and social memory in Skruv. In Järviluoma, H., Truax, B., Kyto, M. and Vikman, N. (Eds), Acoustic Environments in Change. Tampere: University of Joensuu.

Schafer, R. M. (1977). The Tuning of the World. New York: Knopf. Reprinted as Our Sonic Environment and the Soundscape: The Tuning of the World. Destiny Books, 1994.

Thulin, S. (2013). Mobile Audio Apps, Place and Life Beyond Immersive Interactivity. Sound Moves: Journal of Mobile Media, 7(1).

Truax, B. (1984). Acoustic Communication. Norwood: NJ, Ablex.

Uimonen, H. (2011). Everyday Sounds Revealed: Acoustic communication and environmental recordings. Organised Sound, 16(3), 256–263.

Bio:

Milena Droumeva is a sound studies researcher and sensory ethnographer who recently completed her PhD in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University where she wrote her dissertation exploring the way people make sense of their everyday experience by listening to and recording sound. Milena has worked in the general sphere of acoustic ecology and acoustic communication for over 13 years, and is primarily interested in the relationship between sensory engagement with the environment, technological mediation and participatory new media cultures.

Leave a Reply